Unity Technologies

Making Unity Games Accessible

Shipping Unity's first native screen reader workflow for 5+ million game developers.

Role:

Senior Product Designer

Contribution

User Research, Interaction Design, API Definition, Product Definition, Accessible Game Design

Project Outcomes:

+ Published game accessibility standards for 3+ million Unity developers. Shaping industry UI standards to comply with CVAA, WCAG, and European A11y. + Designed UI construction workflow interaction foundations in Unity 6 interface builder module.

When I joined Unity's accessibility initiative, game developers were hacking together solutions that barely worked, enterprise clients faced being pulled from European markets, and the forums were full of frustrated posts from developers who'd tried everything. 18 months later, we shipped a native screen reader API, a Chrome DevTools-style inspection workflow, and an open-source reference game that developers still use today.

This is the story of how I helped define what accessible game development looks like— by focusing on improving the developer game creation experience, and deeply understanding screen reader users input interaction.

Problem: Mobile Game Developers could not get screen readers working on games.

Unity powers about 7 out of every 10 mobile games in the world. When I started on this project, none of them had a native path to accessibility. The forums told the story clearly. One developer wrote a 2,000-word post detailing every workaround they'd attempted. Another maintained a community plugin called UAP that sort of worked, sometimes, on some platforms. Our largest clients—studios building data-heavy games like Football Manager—couldn't get any solution to function reliably. And with the European Accessibility Act deadline approaching, "unreliable" meant "pulled from the market."

30 million+ gamers with disabilities in USA represented a market that indie developers couldn't afford to serve and enterprise clients couldn't afford to ignore

How do you make games accessible? What are game developers asking for?

Accessibility in games is enormous. Screen readers, colour blindness support, motor impairments, game magnification, cognitive load reduction—etc. What main assistive technology should be prioritized? How do we apply it for games?

Consider MiniMotorways (below), which doesn't support screen readers, how would the gameplay adjust for different assistive technologies?

Pictured above: Mini Motorways. A Popular unity game with no Screen reader support. Highlights unique navigation for each unity game

I observed that games aren't productivity software. Part of a game's unique proposition is its unique UI and gameplay framework. A one-size-fits-all accessibility solution would strip away what makes games feel like games. There are main accessibility interactions to solve for but it needed an open/flexible approach, a shared foundation that developers could build on it could give developers an ease to do more accessible games.

When I joined, the engineering team had already begun technical experiments. What was missing was a clear UX direction—someone to answer not just "can we build this?" but "what should we actually build, and what should the workflow feel like?" “How do we know the game accessibility features work with gamers?”

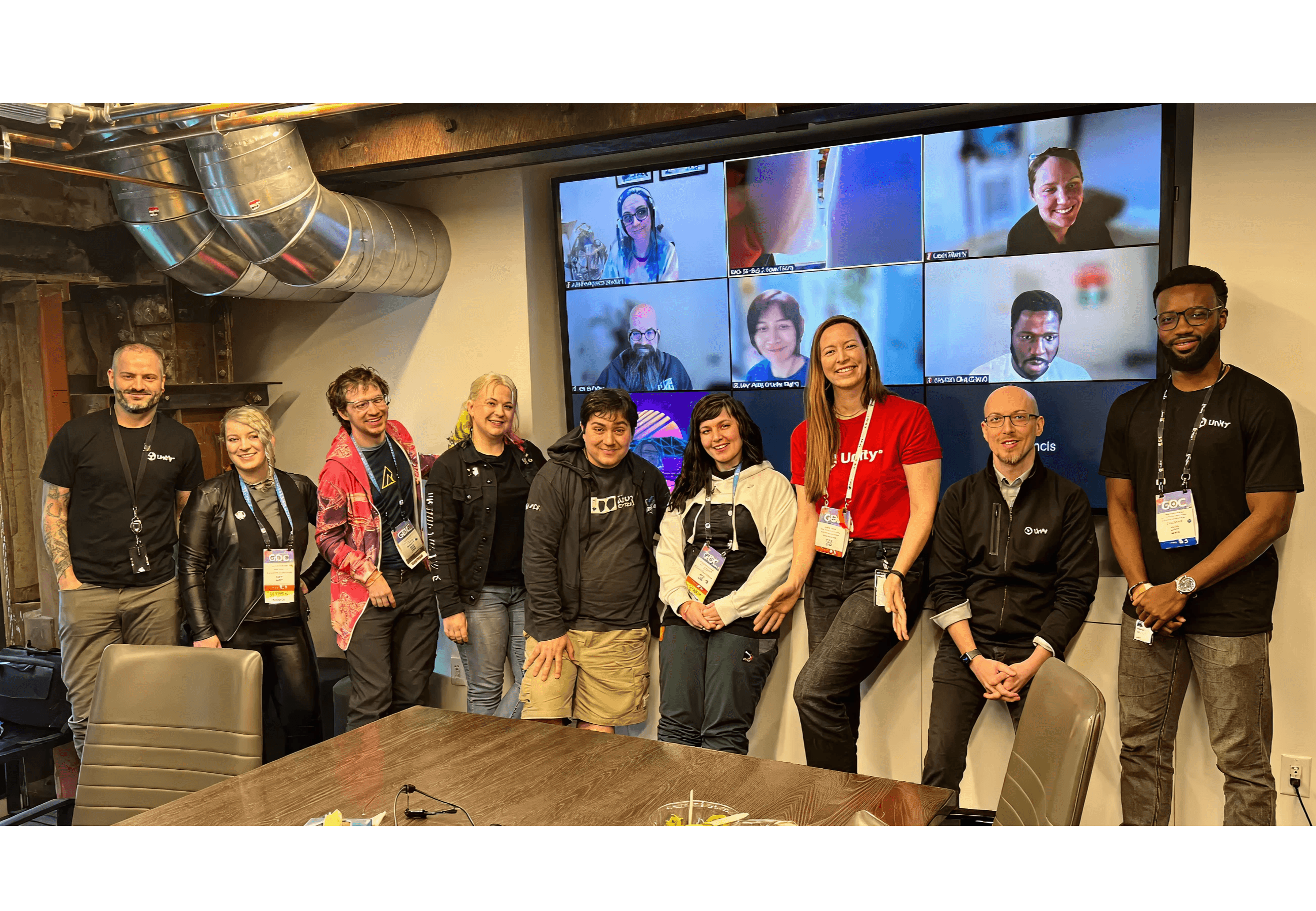

My first contribution was filtering through the technical experiments to create a product point of view to the most impactful experience to our developers and our downstream gamers. I co-led a GDC roundtable where we brought together studio heads, accessibility experts, and developers. We expected conversations to focus on accessibility pain points in Unity developer experience, what we got instead was a wake-up call.

Blizzard had just launched Diablo IV with a custom screen reader implementation, and the room was buzzing about it. Small studio after small studio asked the same question:

"Can we come together as a game community to have a standard? Can we enhance the narration experience in a way that's actually consistent?"

GBC 23' round table participants photo

That conversation crystallized my recommendation: focus on mobile screen reader support first. Not because it was easiest, but because it would immediately change the lives of millions of gamers while giving our largest clients a path to regulatory compliance. We'd build the foundation that the industry was asking for.

Removing obstacles for accessible UI creation.

The UI authoring workflow needed to be upgraded for accessibility data binding.

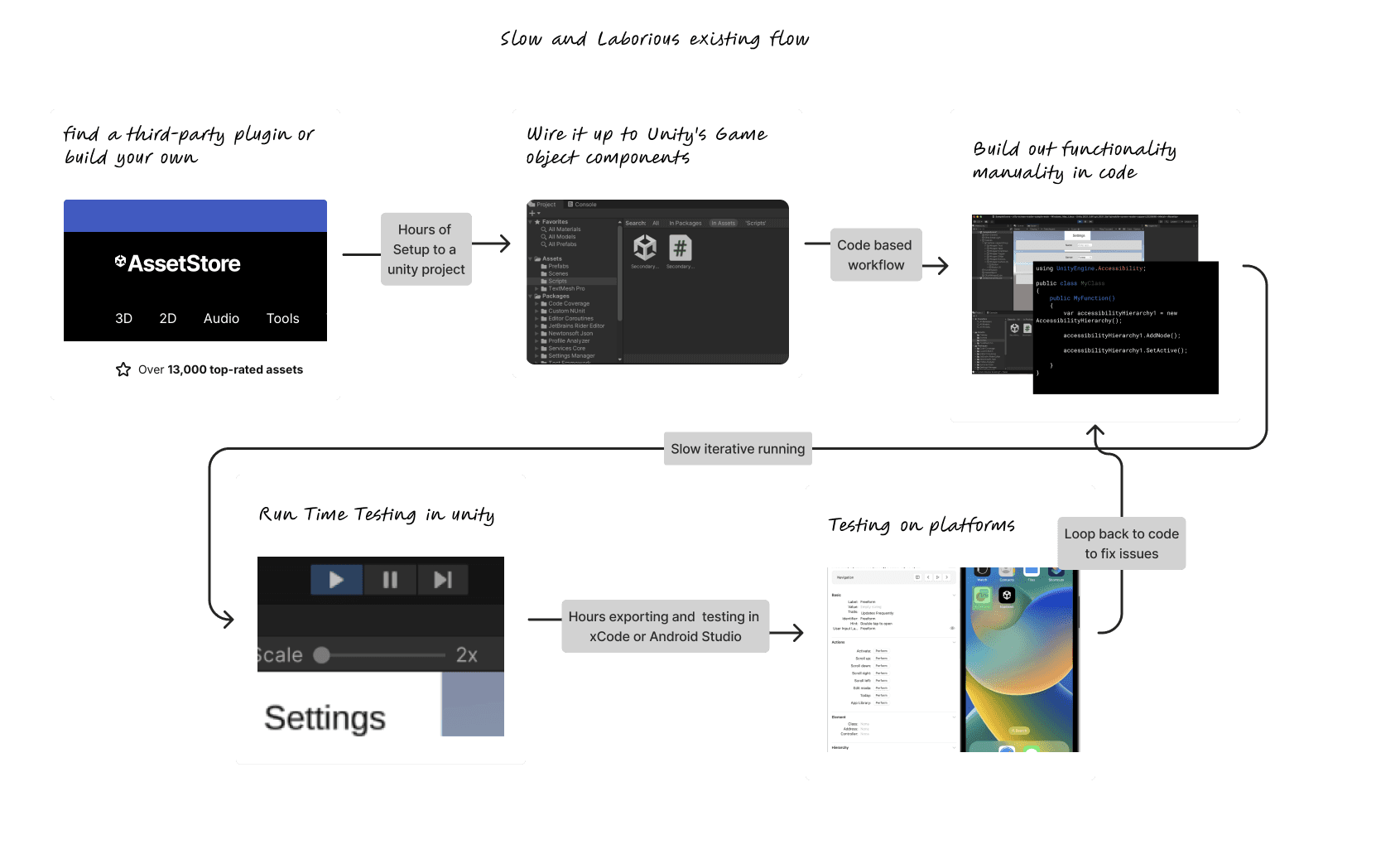

The existing workflow looked like this: find a third-party plugin or build your own, wire it up to Unity's UI framework through code, test iteratively in runtime, build to your target platform, then manually test on an actual device—or skip testing entirely and hope for the best. Every step was friction. Every step was an opportunity to give up.

Obviously- no flexible native functionality

High Friction in context switching

No ability to observe accessibility while building

Code centred workflow creates issues for game-ui designers and testers who don’t code

No guarantees that custom solution followed what screen readers users interaction expectations

Extremely long feedback loops

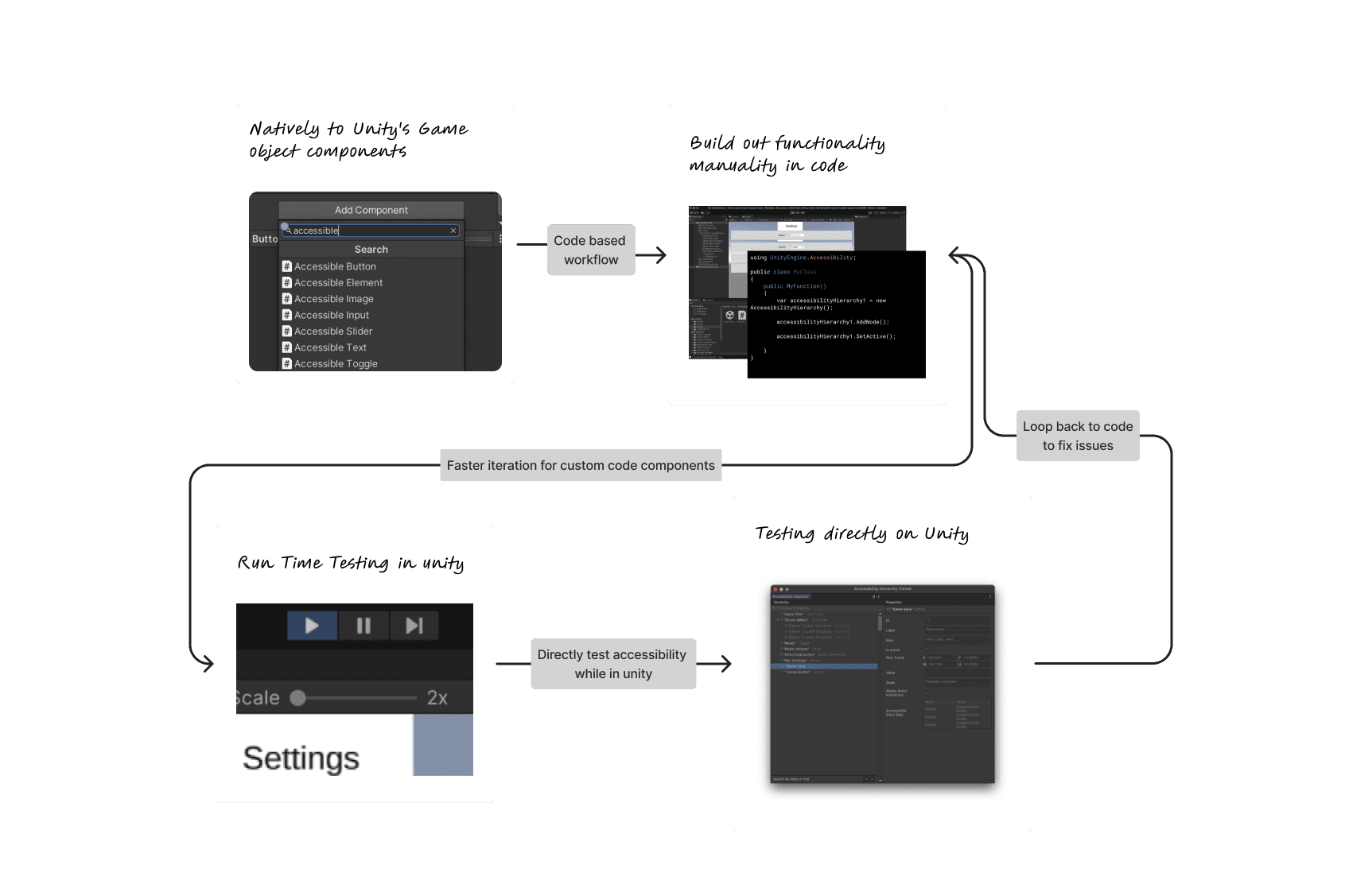

Web developers have had accessibility tooling for years. Chrome DevTools lets you inspect the accessibility tree—the underlying structure that screen readers actually navigate—while simultaneously interacting with your page. You can see what's labelled, what's missing, how focus flows. The tight feedback loop between building and validating is what makes accessible web development tractable.

I wanted that same loop for game developers.

The analogy held in surprising ways. Unity scenes map conceptually to web pages. UI hierarchies map to DOM trees. Game developers already think in terms of nested objects and parent-child relationships. An accessibility tree wasn't a foreign concept— it was a reframing of structures they already understood.

Native accessibility functionality

Conde powered but not code centric - accessibility visible in

Quicker /shorter loop of accessibility review

Testing the workflow by making a game

I couldn't design this workflow abstractly. I needed to feel the friction myself.

Letter Spell started as a test harness. I needed a simple game—something with familiar UI patterns—to exercise the accessibility primitives we were building. A word puzzle game felt right: clear interaction targets, sequential gameplay, state changes that would stress-test our announcement system.

It became my primary design tool as I refined the workflow and the accessible interactions.

Every friction point I hit as a designer building an accessible game revealed a gap in the tooling we were creating. I wasn't theorizing about developer needs. I was living with them.

Defining interaction patterns for an industry

The inspector was the visible work. The harder work was invisible: deciding how screen reader interactions should actually behave in games.

iOS VoiceOver and Android TalkBack handle fundamental interactions differently. When a modal opens, where should focus go? When content updates dynamically, how do you announce it? When a user swipes through your interface, what order should they encounter elements?

These decisions would be baked into Unity's UI Toolkit primitives. Every game built with our framework would inherit them. I was defining patterns that would shape how millions of players experience thousands of games.

Testing with the gamers with visual impairments

I couldn't trust my own judgment on this. I'm a sighted designer who'd taken an accessibility course and spent months immersed in screen reader documentation. That's not the same as living with a screen reader daily. I worked with Microsoft's accessibility testing service to validate our API decisions with actual screen reader users. They played Letter Spell. They broke things we thought were solid. The testing confirmed we were on the right track. More importantly, it revealed gaps. Every session generated concrete changes to the screen reader API and the guidance I gave to developers.

What shipped

The mobile screen reader API shipped as a native Unity feature. For the first time, Unity developers had a supported, documented path to making their games work with VoiceOver and TalkBack.

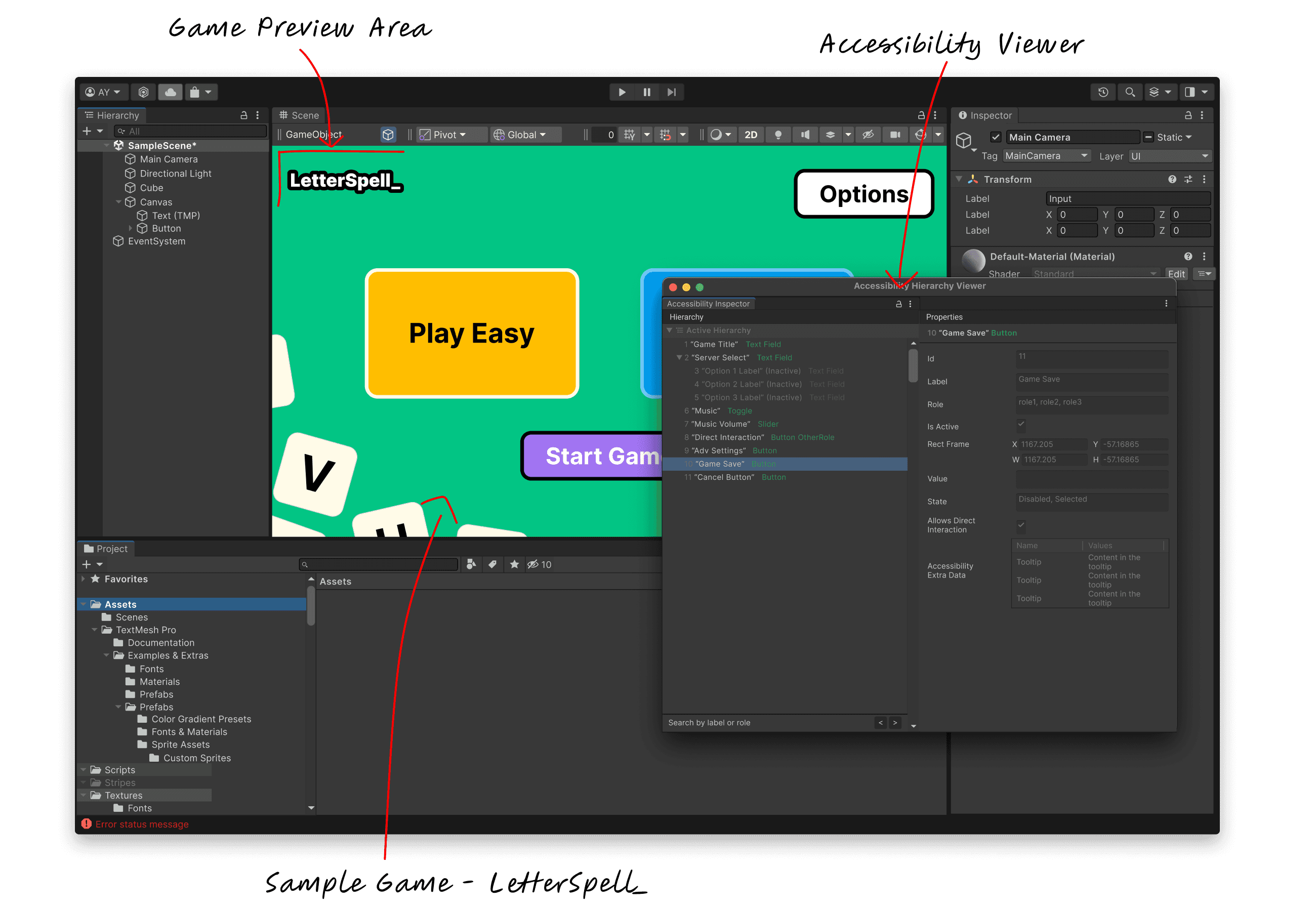

The Accessibility Hierarchy window gave developers a Chrome DevTools-style inspection experience—see your accessibility tree, validate your labels, fix issues without leaving Play Mode.

Letter Spell shipped as an open-source reference implementation on GitHub. It wasn't just a demo—it was a teaching tool showing how to implement accessible interactions in a real game context.

[IMAGE SUGGESTION: The official Unity blog post header, linking to https://unity.com/blog/engine-platform/mobile-screen-reader-support-in-unity]

Contact Seyitan to keep reading

© 2024 made with figma & framer